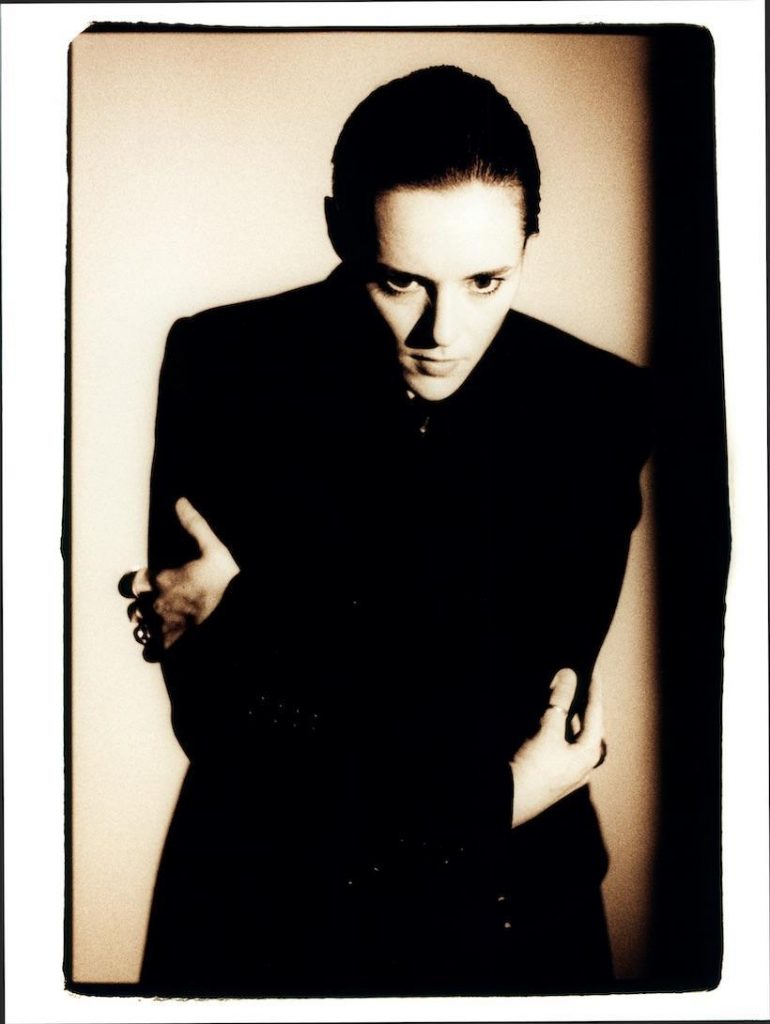

To Love Is To Live: Jehnny Beth

Jehnny Beth challenges gender norms and uproots social norms through her raw self-expression and empowerment which is most evident in her latest solo record, To Love Is To Live. It is filled with Beth pushing up against stereotypes and disrupting conventions all with a sense of urgency that makes the sound and messages of the album all the more potent.

Born Camille Berthomier in Poitiers, France in 1984, she initially trained in dramatic arts at the Conservatoire à rayonnement régional de Poitiers. Having fronted the band, Savages, alongside collaborations with Gorillaz, The XX, Julien Casablancas, and Trentemøller, she is well-regarded and deeply established in the global rock music scene. Beth has turned her hand to radio presenting (she runs her own Beats 1 programme called Start Making Sense), television hosting, writing, and acting.

After successfully mastering the art of being the modern multi-hyphenate, Beth shared with FRONTRUNNER her creative process, her new record, and her personal music recommendations.

How would you describe your musical process and did it change when making this record?

First off, I just want to say that I decided to take my time with this record, I didn’t want to rush it. I wanted to change the way that I had been doing things. I wanted to collaborate with new people, get influenced by them and just learn from them also to learn new methods and try out new things. The way I worked on the record was quite fragmented in a way, and when I say that I was allowing time it was because I wanted moments where when we listened to anything we had recorded, we would be able to forget about it to come back to it. With time, I wanted the music to sound effortless. I didn’t want to force it or to push it in any direction. I wanted the songs to develop by themselves and not just by me imposing on them what I thought they had to be in a way and for that I needed distance and I kind of prefer to work that way. In between recording sessions, I would still be creating but in different ways and that’s how I ended up writing a book.

I started writing on my own, so the lyrics were the first things that I was set on early on, and didn’t change much. Except for a song like “Heroine”, where we really shifted the song completely in the studio, lyrically. So lyrics were the first thing, and I remember having the lyrics for “Innocence” and “I’m The Man” really early on. What I wasn’t sure on was what musical expressions they would be left on and a good thing I did was to go into the studio with Johnny Hostile and we tried many many versions of the songs, sometimes we would have five or six versions for one track. The idea was to try to explore and do a lot of research into the sounds we kept sort of like lab work. We wouldn’t set boundaries on the genre and if we wanted it to sound like a drum-and-bass track, we would do it. We wouldn’t try to pull back, you know? So we have these patches of sound and some of the songs were kept that way like “We Will Sin Together” a song that we did that way, Johnny Hostile and myself. Then some songs needed more work.

What it was like working with Atticus Ross and how did he influence the record?

Atticus Ross was the first producer that we worked with. He didn’t do any music for the first six months of our conversations about him working on the record. We would meet in LA, me and Johnny Hostile we were only there for like 3 months at some point, working in the studio there. At that point he would come by the studio in the evening, giving an opinion, directing what was needed in general and playing some stuff. Then we started work on “I Am” which is the intro track of the record. At that point, we came back to Paris and then carried on working on it and he sent us the first draft and what was amazing was that the first draft was very close to what you can hear on the record. He basically spent so much time with us trying to understand what we wanted to do and he wanted to make sure we were going in the right direction. And when he nailed it on the first round, we then worked with him lots after that. What he did was really put the record in another direction and what he did was really lift the record into a different dimension. I would say that he gave to the record a sense of journey and drama and that was exactly what I wanted and what we had been talking about. His first question was are you making a collection of songs or are you making a record.

How did you begin working with Flood and how did you work together?

I started working with different producers and nothing really stuck. Then PJ Harvey said, “Why don’t you try with Flood, because it seems you need a producer for some songs that is more rock”. The first song we started working on was “Innocence” and for a few days it was a car crash, I hated it and he was confusing me and he was doing it on purpose and I have learnt how to work with Flood but for the first few days it was a smack in the face and a great reminder of what it means to get lost which is I think, a problem with making records these days it’s so expensive booking a studio and it sort of kills your creativity being in a studio because every minute counts and suddenly if you feel like you are going in a direction that feels like you’re lost then the instinct is to walk back. But when you make music at home you allow yourself more time and you know you need to make three bad turns before you make the right one and you never really know when that is. But Flood never really forgot that and the older he gets, the more he wants chaos, he’s a master of chaos really. So after those few days, I was on the edge of losing it and he asked me to leave the studio and then asked me to come back an hour later then he did sort of a live mix and everything came together and I was like oh that’s what we’ve been doing and it was sort of magical. “Innocence” came out of that, and I did the “The Rooms” with Flood.

As a writer, musician, radio presence and television host, you seem to have many creative projects on the go. How do these creative ventures fit together for you?

One of my heroes who is multidisciplinary is Henry Rollins. I always recognise myself, if I can say that humbly, in the way that he would be able to be the frontman of really great projects; being his own solo artist but also having a tv show, doing podcasts, radio and acting. And I always felt like that was how I felt about my own creativity, even for writing. I like new experiences, I don’t want to feel like I know too much and I love the idea of figuring it out as you’re doing it. I like working with fear and being at odds with what’s going on and not being sure I can do it. I like new beginnings as well. I think sometimes people put the best out of themselves when there is a feeling of risk. I don’t really like routine and I’m just curious. The reason that I do radio and TV (I have a TV show called ECHOES with Jehnny Beth, where I invite artists to talk and perform with an audience) is because I do it naturally in my life. I like to interrogate artists about the process, and I think learning about the process is very important.

What inspires you the most and feeds your creativity?

My relationship to Johnny Hostile is very inspiring as I’ve known him for years and we’ve always been artists together and he was the first person who gave me the confidence to even name myself as an artist. The way we lead our lives is that when everything is okay we like to be creative together and also separately. I’d say that everything is okay because I never want to give the impression that creation is easy and available all the time. When you wake up in the morning, when there are bad and good days, I do believe that you have to train creativity like a muscle. The same way that when you exercise and stop it is harder to get back into it again. I try to have a life that is giving me inspiration and people who are feeding me things. A big thing about being an artist is feeding from others and it’s not as in taking but in being a sponge. You can’t really stay in the position of the fan if you like someone else’s work it is important to find out how they make it because if you want to make the same kind of work someday or your own on the same kind of level, you need to be interested in what’s behind it, not just be a receiver. It’s like Leonard Cohen said, “If I knew where the good songs came from, I’d go there more often.”

Do you think your best ideas are your first or last ideas and how did this impact the production of the record?

It’s interesting because when I think of the work we have done for the record and what is on the record, I would say that 10% of what we have done made it onto the record. And that is rare, I have done that before in other creations but this feels like the first time I have produced a lot of things and only kept what I felt was really the best. When I worked with Romy Madley Croft, for example, who co-wrote some of the songs, she worked with me on some lyrics and we were just having fun, we were just friends who liked to write and learn methods together and play each other demos. It was that kind of relationship. But literally, 90% of what we have done is not on the record but it doesn’t matter because it’s just the way I like to spend time as well. I like it, but not all the time. Sometimes people ask me, “How do you feel in confinement?” I say it doesn’t really change anything. I’m not the kind of person who really goes out on a Saturday night. I spend my Saturday nights filming the back of my hand, you know. So this is not different for me.

What is your process when translating a song into a stage performance and do you ever write songs with the live performance in mind?

I didn’t write the record for the stage, I felt like if I was going to do that then I was just going to repeat myself. So I decided to continue to forget about the stage but when I had to take to live performance again it was almost like training and I had to go back to the songs and think how do I do this, it’s interesting because we worked on that for six months before everything shut down. We were working on expanding some parts of the song and creating a whole other world of the record but I think of the live performance as a real, free expression of the record. We had a lot of freedom in that and fun, but I always knew like “I’m The Man” was a track that I was excited to perform live. I like to embody stereotypes especially on stage, I think its very fun. I always thought that on stage, I wanted to be able to draw like with one line, which you can do if you’ve got a silhouette that you are able to draw with just one line, then you’ve got it.

Are there any artists that you recommend we listen to?

I’ve got two names in my head. There’s this French artist who lives in LA called Sofia Bolt who makes really sweet records. There’s also Jorja Chalmers, she’s a saxophonist for Bryan Ferry and released a solo album recently. She actually plays the saxophone on “I’m the Man.”